Out of the Ordinary

Susanne Kircher is a human geneticist. She deals with rare genetic metabolic disorders that cause physical abnormalities. An absolute luminary in her field, she graciously makes an effort to present the most complicated facts in a way that laypeople like us can understand. A conversation about God, genes, and gargoylism.

“There are no mistakes, ideally we would call them variants.”

Viktoria Kirner: Thank you for inviting us to the Center for Pathobiochemistry and Genetics here at the Medical University of Vienna. You seem a little out of breath, have you had a stressful day?

Susanne Kirchner: You know, I only really began being stressed out when my husband retired (laughs). I’ve had the feeling ever since that he’s just sitting at home in his armchair with a stopwatch, waiting for me to get home. But a doctor’s workday just isn’t compatible with a stopwatch.

Your work addresses rare genetic disorders. You research gene pools—a collection of different genes—and seek out those that are “defective.” How many genetic mistakes does nature make?

I wouldn’t call them “mistakes,” because mistakes always suggest that something is wrong. Ideally we would call them variants. At present, we know about 25,000 genes, of which about 7,000 can be attributed to a disease. All told, however, a human being has hundreds of thousands of different gene variants that distinguish him or her from other human beings. You could say that every human being is the sum of their individual variants.

How does someone become a geneticist?

I took a few detours getting here, from gynecology to pathology and finally to laboratory medicine. When I began my training at the university, I was entrusted with an extremely unusual case: I had to examine urine samples from people suffering from what is known as “gargoylism,” which is actually called mucopolysaccharidosis. The faces of people with this disease are deformed and resemble those of gargoyles, hence the common name. So I somehow stumbled into the field of rare genetic diseases with abnormal physical manifestations. I was fascinated right from the start.

So “gargoyles” laid the foundation for your fascination with the “genetically unusual”?

The foundation was actually laid a bit earlier. As part of my pathology studies, I had to perform an autopsy on a young woman who had died of internal bleeding—one of her blood her vessels had inexplicably torn. The examinations had shown that she had a rare genetic connective tissue disease known as “Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.” This disease has been known for well over a hundred years, but the research on it is still in its infancy. This unusual disease continues to occupy me to this day.

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome? I’ve never heard of it, can you tell me about it?

I’m not surprised. Very few doctors know anything about it. The bodies of people with this syndrome don’t produce enough collagen. Their connective tissue—the natural corset we all wear—is fragile and flaccid; it doesn’t provide the necessary support. The body collapses on itself, resulting in spinal instabilities, herniated discs, disorders of the joints, or dislocations. With certain types of EDS, however, the organs and vessels can also be affected, such as in the case of that young woman. Others lose their teeth or develop ruptures in their eyeballs.

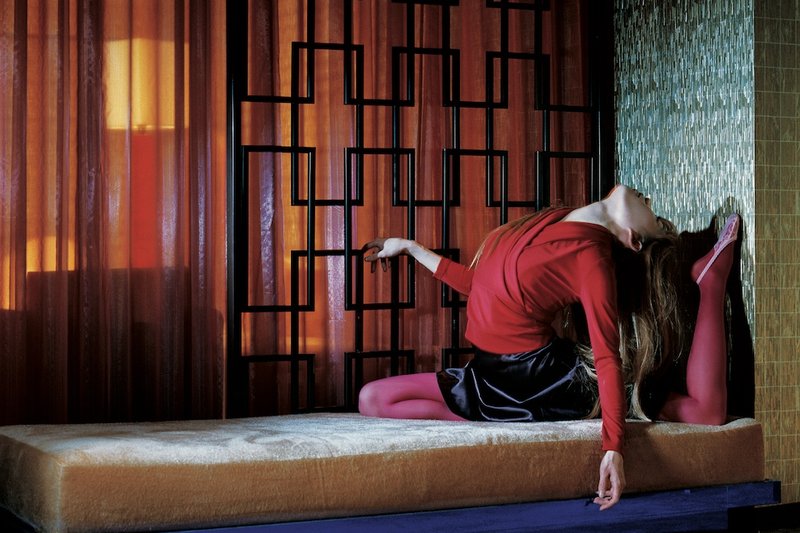

“People with hypermobility were long regarded as an exotic circus attraction.”

How is it possible to have never heard of a disease that affects such absolutely crucial parts of the body?

Do you know where you might have seen people with this disease? In the past they were often put on display as contortionists. Their skin is extremely elastic, the tendons and ligaments are very limp, so they are extremely flexible and mobile. People with hypermobility were long regarded as an exotic circus attraction.

So all those unusually flexible circus acrobats are actually suffering from Ehlers-Danlos syndrome?

In the past, yes, but not anymore. I am pretty sure that the contortionists who were once exhibited in circuses or so-called “freak shows” had EDS or at least some other form of connective tissue disease. They had this peculiar trait without being specially prepared for it. The people you see in the circus today have rigorously trained their bodies to be able to pull off these incredible performances.

We are equally fascinated by physical perfection and imperfection. Where does this voyeurism regarding physical abnormalities come from?

People have always been attracted to the unusual and the novel. At the end of the 19th century, the Vienna Prater featured what were essentially “human zoos.” In the 1890s, the African “King Ashanti” and his village were kept in cages there like wild, exotic animals and displayed in front of thousands of visitors. History is full of similar examples. One of humanity’s lowest points, if you ask me.

So people who looked different were primarily used to satisfy our curiosity?

In some cases it wasn’t just a matter of satisfying curiosity, sometimes different-looking people also fulfilled other “functions.” People with dwarfism were often highly regarded, for instance in the age of monarchy: Many were extremely clever and were “kept” by the rulers as trusted advisors. They were the only ones who were allowed to speak their minds freely. Unlike other people, they were supposedly not dependent on the favor of the ruler, since they already had an unusual status in society due to their abnormality and therefore had nothing to lose.

Have you ever seen Game of Thrones?

No, why?

The dwarf Tyrion Lannister is “Hand,” or closest advisor to the queens and is portrayed as the most intelligent character in the series...

Well, there you go! From an ethical and moral point of view, of course, things like that should be considered critically.

What kinds of ethical or moral conflicts do you and your colleagues find yourselves confronted with?

In counseling, we sometimes hit a wall when it comes to faith and religion. There are patients who have a serious genetic disease and who are very likely to pass it on to their children. But they regard their illness as “God-given,” and if they were to pass it on to their child, that would be because it has been divinely ordained. It is very difficult to council such people, since they believe God wanted it that way.

“I believe in an energy that governs us.”

What is your opinion on God? Can a human geneticist believe in divine creation?

I worked in pathology for a long time. That was where I realized that there has to be more to things than just this mortal shell. This might sound a little mystical, but the stories people tell about near-death experiences—I felt that so often in the dissecting room. I was alone with the deceased, but I wasn’t really alone. I believe in an energy that governs us. Who controls this energy, where it goes after death, whether it is released into the universe afterwards—the answers are beyond the scope of my knowledge. As a geneticist, I try to explain everything that I can see and grasp, but deep inside I know there is much more. Perhaps that could also be a god.

Is there gene you would consider “perfect”?

I don’t think there is a perfect gene, but perhaps a perfect gene pool—in the sense that it doesn’t cause disease.

What do you personally consider the most serious genetic defect?

Genetic defects are always bad when they go undetected. Something I find particularly troubling is watching young Ehlers-Danlos patients become marginalized socially. Not only do their physical impairments often prevent them from pursuing their profession or going out among people, they are also frequently not taken seriously. Living with untreated symptoms for long periods inevitably brings about psychological comorbidities such as depression. Once these are diagnosed, many doctors declare the actual genetically caused physical problems to be psychosomatic. A vicious circle that sometimes drives patients to suicide.

“I consider gene therapy to be one of the most sensational discoveries ever.”

Which story has affected you most in recent years?

Also very difficult for me are cases where, in the course of providing genetic counseling for an entire family, I see one relative after another dying as a result of their inherited genetic defect. Even after doing this work for 35 years, it is still very hard to take.

Gene therapy technology has made incredible advances; gene editing, as it is known, is opening doors to previously unheard-of therapeutic possibilities.

To what extent can “sick” genes be cured?

I consider gene therapy to be one of the most sensational discoveries ever in the field of genetics. In the future, it will be possible to offer people individualized treatment by influencing their genetic make-up. Gene therapy is already being used to alleviate or stop the progression of a number of diseases. What is known as “stop codon readthrough” therapy, for example, is already showing initial success in cystic fibrosis patients.

What exactly does that entail? Can you just grow healthy genes in a Petri dish?

Almost. In the case of certain diseases in which a defective gene cannot form specific gene products, there are now drugs that can be administered so that a certain gene product is formed or made available. However, gene therapy also means that, while defective genes are left in the body, correct genes can be introduced via viral vectors. That is, if your own gene cannot form the desired gene product, the newly introduced gene can. This is revolutionary. There are great things in store for us in the future.

But these editing functions are not only used in gene therapy. Through the use of what are known as CRISPR technologies, scientists now have a tool at their disposal with which they can create specifically designed organisms. It is already theoretically possible to alter genes within ova or sperm cells.

We could create our own “designer babies.” Don’t the technical developments in genetics make you a little queasy?

Fortunately this kind of birth control or preimplantation genetic diagnostics is not permitted in Austria. But genetic manipulation of embryos is already being carried out illegally in some countries, China among them. Genetic assets are manipulated or embryos are “selected,” which is morally and ethically very controversial. This subject really does make me a bit queasy—there are still many fundamental questions regarding genetics that need to be answered first.

If your parents had been able to design you as an embryo, what characteristics would you have wanted for yourself?

I’m pretty satisfied with the traits I inherited naturally. My parents both lived to a very old age, so I hope they passed that on to me. At least that way I’ll have a few more years to spend with my poor husband once I’ve retired (laughs).

Your husband is looking forward to your retirement?

And how! Though I’ve already gotten him to make at least one concession, that I’ll still be allowed to think when I’m retired. I’m sure I’ll still be publishing scientific papers as well. After all, I still have all that knowledge inside me. Where else is it supposed to go? Out into the universe?

Thank you very much for the interview!