"Computing affects all forms of life."

At the Creative Days Vienna, which are part of the ViennaUP Festival, she delivered a keynote speech on the connections between biology, technology, and digital culture – topics that are also at the core of her journalistic work.

Magdalena Willert: In what situation are you completely analog?

Claire L. Evans: I like to get dirty when I'm gardening. I don't use gloves, I get dirt under my fingernails and carry it into the house on my shoes, I get splinters and I don't care about insect bites.

How do biology and technology go together?

That's a matter of definition. Our understanding of technology today is very one-dimensional, technically characterised by the history of computer science as an industry. But ‘computing’ is much more than that. Every living being does it.

ChatGPT defines ‘computing’ as follows: "Computing is processing, managing and analysing information. It encompasses a wide range of activities, including programming, data processing, algorithm development and the use of software applications to solve problems or automate tasks." You mean something else by computing, don't you?

The act of computing, or rather information processing, can be applied to almost anything, everything and every living thing that acts dynamically in the world and thus shapes reality.

Do you have an example?

Think of a worm. It is a simple organism, but in order to survive it must process and store information from its environment—things like temperature, the presence of food and predators. When it makes decisions based on this information, this is also a form of ‘computing’. We have tried to create computer models of these basic functions of a worm’s brain—it’s extremely complex, and takes enormous computational power. But a worm does it with hardly any energy at all.

"I prayed to my grandparents' dead dog."

Claire L. Evans installed a worm on her computer — and no, that’s not a metaphor. For her March 2025 Wired magazine article ‘The Worm That No Computer Scientist Can Crack’ she delved into the OpenWorm project, which aims to fully simulate the microscopic nematode C. elegans. With its tiny nervous system and just 302 neurons, this worm could hold the key to a deeper understanding of both biology and technology.

What else can the tech world learn from nature?

Ant colonies use algorithms that work in the same way as our internet data routing systems. Slime moulds find the most efficient paths through uneven terrain. Our network design can learn from this. The more we learn about such organisms, the clearer it becomes: Much of what we think are human inventions have existed in nature for millions of years. If we put our ego aside, we can learn an incredible amount from them.

You were brought up atheist – what kind of impact did that have on you?

Nothing special, we never talked about that kind of thing. Although I do believe that children need some kind of spirituality. So I invented my own rituals because I knew there was something bigger. I prayed to my grandparents' dead dog, even though I didn't even know what “pray” meant.

How did you grow up?

I was an only child from an immigrant family in the US. My mother was French, my father British. I was more of a loner. I didn't get on badly with other children, but I liked being on my own. I made up stories or sometimes just stared at the ceiling. This boredom was almost meditative. I still like being alone today.

"Ants use algorithms."

As a tech journalist and musician, you've been observing AI pretty much from the beginning. You were one of the first artists to work on an album with the help of AI in 2017. How has your perception of AI changed over the years?

As a sci-fi fan, I used to think AIs were humanoid robots with consciousness. When I worked with them myself, I realised that it was just complicated mathematics. I tinkered with AI by chance at a particular moment of transition, when it was still primitive and interesting. You had to intervene as a human to get something useful. I found that thought comforting.

Do we no longer need humans today?

I think human intervention is still needed to make something interesting. Today, however, these tools present themselves as if they can do everything with little user input.

Are you worried about technological developments?

Yes, I've seen how pointless things have been done with these tools. I've seen evil being justified, but I've also seen wonderful things. So I'm not a technophobe. I see it more like language.

A language that we have to understand first?

Historically, we've had more time to understand such huge technological changes, such as photography, which took a century to get rolling. We’re still working on questions such as: What is a photograph, what is reality? Today, these changes are happening rapidly and constantly – too fast to categorise and understand.

"AI generates boring stock photos."

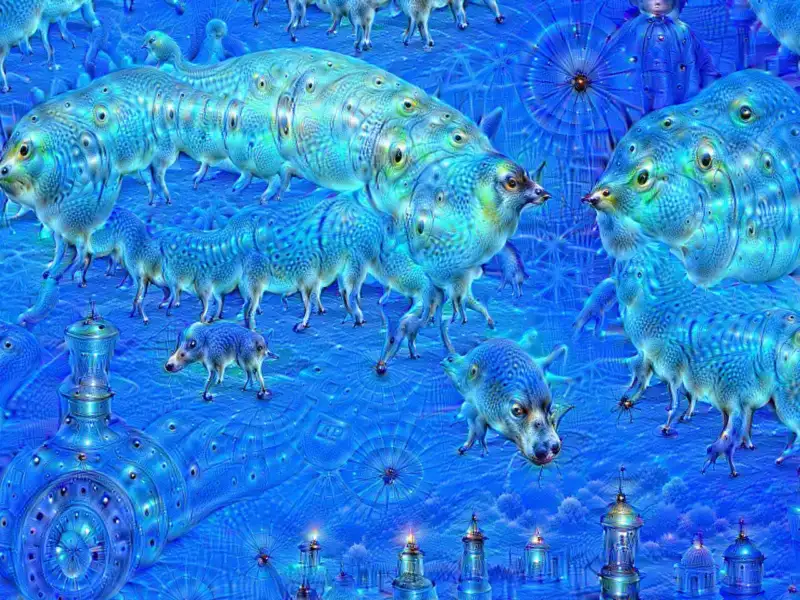

"One of the first major AI-generated images to emerge in 2015 was Google’s Deep Dream. It generated these images that were absolutely crazy and grotesque." (As you can see here...) "The system over-identified images, basically like a reverse image algorithm. It felt like another kind of consciousness or intelligence was creating these images. There's no human being behind the wheel here. I think this is an example of a particularly crazy early AI thing that is now lost forever."

You documented the production of your AI album. This resulted in the film ‘The Computer Accent’ in 2022. What accent does a computer speak?

The appeal of AI back then was how quirky and unpredictable it was. Whether you were generating images, text or sound, it always felt like it was coming from a computer, with that unique soft accent. A tone of voice that somehow sounds wrong. But that accent has disappeared. It's as if the computer has learnt our language much more fluently.

Could it only stutter back then?

One of the first big AI machine-generated images to emerge in 2015 was Deep Dream by Google. It generated these images that were absolutely crazy and disgusting. It was completely unlike anything a human would ever create, which I found endlessly captivating. Today, AI just generates boring stock photos.

You've been playing together in the pop band YACHT for over 20 years. Do you like big boats?

No. The name is a bit embarrassing – YACHT sounds like luxury. But it comes from a dilapidated building with the sign ‘Young Americans Challenging High Technology’. My partner, who founded the band in 2002, was so fascinated by this enigmatic but also symbolic scenario that he named the band after it.

"The computer accent has disappeared."

The band YACHT was founded in 2002 by Evans' partner Jona Bechtolt, in 2008 Evans became part of the band as lead singer. YACHT began working with artificial intelligence on their album Chain Tripping in 2017. They used AI models to help co-create lyrics, melodies, and even cover designs.

Are tech tools still part of your band?

Yes and no. Not as Luddites, but in dialogue: How do we use tools to make art that is bigger than ourselves? We made an AI album in 2017. The lyrics, the cover, the videos and the merch were also created with AI. That was a one-off experiment. After that, we no longer wanted to be an ‘AI band’. Now we're in a ‘post-AI’ phase and are going back to being more human.

Do you use ChatGPT a lot these days?

Why is that?

I don't find it interesting. When it was still rather bad, I found it exciting to figure out how machine learning interprets input that it doesn't understand, how it messes up all these variables and presents you with a guess about what it thought you wanted. These were ideas that were just bizarre and very inhuman, but poetic in their own way. The dialogue between the human and the inhuman is what really appealed to me about working with AI. And now these tools are just too good.

You are co-editor of the sci-fi short story magazine and anthology ‘Terraform’, which takes a critical look at a potential near future. What is dystopian science fiction good for?

Recognising real dangers through fiction – and taking countermeasures. I'd rather read about a fictional dystopian future than actually experience one.

"For 20 years, the internet had a phone number."

Evens regularly gives talks–both at Computer Science conferences and at music festivals. In 2022, Claire published the anthology Terraform together with Brian Merchant.

Which story could become reality?

Tim Maughan describes a scenario in the US that brought the production of iPhones back to the United States due to a trade war. The only way to make this economically feasible is to have prison inmates build our phones. It's also a love story about an inmate trying to hack into a mobile phone in this factory to send a message to his sweetheart.

How do you use technology, for example your mobile phone, in your free time?

Badly, but I'm working on it. Instagram is not good for me, and I only download it when I need to post something for work. Then I delete it again. In the meantime, it's no longer important to me to reach an audience of millions at some point. I'd even prefer to work on my article for months, get paid and have it disappear into a drawer without ever being read. I want to learn new things through my work, and the audience is secondary.

Your TED Talk in 2015 is also about this: You want the ‘smallest audience’ – is that still your mindset?

Absolutely! The best life hack for creative work: never think about what others want, otherwise you'll go crazy.

You wrote a book about women who made tech history: Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet. Why did you do that?

Simply because I couldn't find any information about them anywhere. So I started looking for their names – often they were only in footnotes or as the fifth author of some paper. The more I talked to these women, the clearer it became: There was this huge untold story. Women who were there from the beginning, who made crucial contributions and then were ignored. I see the book as a kind of corrective.

"Technology was women's work?"

Her book The Broad Band – The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet (2018) serves as a corrective to the previously undocumented stories of women who shaped the digital age. It tells the stories of women like Ada Lovelace, the first programmer, and Grace Hopper, who developed the first computer compiler. Her work was listed among The Verge's ‘Top 10 Best Tech Books of All Time’ in 2023 and Inc.'s ‘Top 10 Best Nonfiction Books in Technology‘ in 2018.

In what way?

Before the web, when the internet was used more for academic or military purposes, there were no search engines. If you wanted to find information, you had to call the Stanford Network Information Centre. There was a woman on the phone who was the only person who knew what resources were available where. She was Google before Google existed. For 20 years, the Internet had a phone number and if you called, a damn smart woman would tell you where to go.

So technology was women's work?

Often. Early female programmers? All women, because programming was considered ‘secretarial’ work until men recognised it as valuable. The network information centre? Indexing information was considered unimportant, like filing work – until search algorithms became valuable and Google built an empire on them. In every tech era, there have been women who invented things and were ousted as soon as their inventions became ‘valuable’. This is a lesson for all fields.

How could we break such patterns?

That's the interesting thing about AI: it is based on historical data sets, on the entire corpus of human creation. This is an opportunity to examine our past: Who are we? What does this data represent? How can we prevent ourselves from repeating the same problems? Sure, the amount is overwhelming – but much like with our history, we can analyse it or stumble blindly into the future.

This article was created in friendly cooperation with the Vienna Business Agency. A fund of the City of Vienna.

Claire L. Evans is a writer and musician who explores the connections between biology, technology and culture. She writes for the Grow, WIRED, MIT Technology Review, NOEMA and The Guardian, among others. She is the lead singer of the Grammy-nominated band YACHT, who also released the documentary The Computer Accent in 2022. She is co-editor of the speculative sci-fi format Terraform and author of the book: Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet (Penguin, 2018), which was translated into six languages and named one of the Top 10 Best Nonfiction Tech Books of All Time 2023.

---------------------------

On 14 May 2025, the opening event of Creative Days Vienna 2025 took place at The Hoxton Vienna. Claire L. Evans and Sean Bidder were this year's keynote speakers. She gave a keynote speech on the connections between biology, technology and digital culture.

They are part of the startup festival ViennaUP and mark the beginning of Content Vienna, the competition for digital design. Over the two days, there will be lectures, tours, and networking events focused on technology, culture, and society.