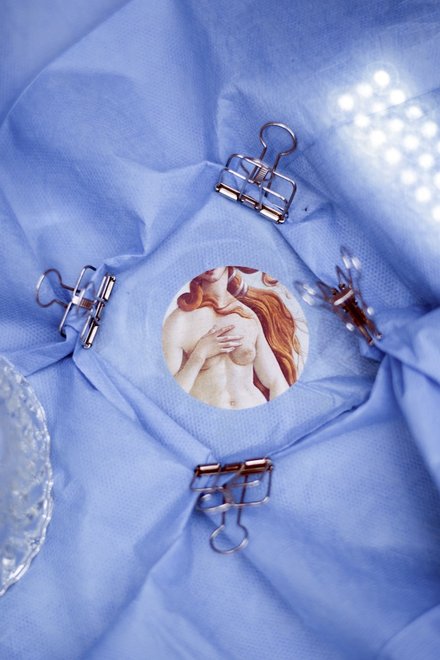

heart and soul

The pulse rises. The heart beats. Hands are sweaty. Breathing accelerates. That’s how it feels to fall in love – or a tachycardia, a racing heart. The most beautiful of all organs can love, hurt, break, and stop beating. It stands for our deepest desires, and in many cultures it is seen as the home of the soul. Only those we take into our heart can have a look into our inner self – or heart surgeons. That’s probably why Johannes Gökler, assistant doctor at the Division of Cardiac Surgery at AKH Vienna General Hospital, has a more pragmatic attitude toward this organ that keeps us all alive. In our conversation the former Armani model tells how fast a heart transplantation has to proceed, what happens to “defective” hearts, and whether a new heart makes you a different person.

“Adrenalin is the key in heart surgery.”

Lena Stefflitsch: What do you find fascinating about a heart?

Johannes Gökler: It is extremely beautiful. Operating on the heart, the surgery, is very precise and clean – sure enough, there is blood, but the work is still quite tidy. Although heart surgery primarily concentrates on one organ, the heart, it is one that effects the entire body. Sometimes general surgeons, who operate on many organs, might smirk a bit…

You are smirked at for operating on the heart?

Well, that’s more this jokey bickering between general surgeons and heart surgeons. We, in turn, also make fun of the others, like: “The kidney is just there to pee, the heart can do so much more!” But of course we are all well aware of how essential every single discipline is. In cardiac surgery one definitely has to be very well informed about the organism as a whole and understand the relationships. The transplantation itself naturally adds another kick. Adrenalin is the key factor in heart surgery.

“The maximum time for transport is two and a half hours.”

Everything has to go incredibly fast with a heart transplantation. How can we imagine this?

A call, the organ donor, kicks off the planning and organization of the transplantation. The entire transplantation takes place under enormous time pressure and all within a few hours. Sometimes, when the distance from the donor hospital to ours is too far, the heart has to be picked up with a helicopter. The pressure is great – in theory a lot can go wrong. After removal the heart is temporarily paralyzed with a special liquid so it does not beat and transported refrigerated. There is not much time to implant the heart in the recipient. No more than four hours should pass between when it is paralyzed in the donor and when it starts beating again in the recipient. Thus, the maximum time for transport is two and a half hours as the implanting takes approximately 60 minutes.

Who are these organ donors? Is the cliché right that they are usually motorcycle accident victims?

That’s not true anymore, at least not in Austria. When the accidents are too heavy the organs don’t qualify anymore for recipients. The typical donor is brain-dead, often after a cerebral hemorrhage, but the heart is still healthy. In most of the cases the donor is already in intensive care for several days, and only then is there thought about whether the patient could be a potential donor. Only patients with an irreversible damage of vital centers of the brain come into consideration.

How long is the waiting time for a heart?

The waiting phase can last up to one year, for the most urgent cases only a few days. Unlike Germany we are “blessed” here in Austria with a good donor-recipient relation. In Austria one is automatically an organ donor in case of accidents; in Germany active approval is required.

Is the patient allowed to know from whom he/she received the heart?

In Austria it is not legal to be informed about the donor. Often there is great desire and sometimes even a strong urge to learn who the organ belonged to previously and to get to know the friends and family of the donor. This feeling of the patients is perhaps similar to that of not knowing one’s own parents. Some want to express their deep gratitude.

In the USA one can learn about the donor upon request. A father of an organ donor rode across the USA on his bike to meet the recipient of the heart of his deceased daughter and hear her heart beating one more time. Naturally, the whole thing was blown up by the media. But this story still gives me goose bumps.

What happens with the “defective” heart, is it – quite unromantic – automatically disposed of?

The removed hearts often have functioning heart valves; they are cut out and prepared for re-use in other heart operations. Everything else is sent to the pathology department and closely examined for the cause of the heart disease.

How many surgeons are in the operating room during a transplantation?

Usually there are three of us, and there is the heart harvesting team consisting of at least two surgeons. A heart transplantation is considered a relatively simple operation as the heart is “only” sewn onto the largest blood vessels of the body. Other cardiac operations require a much more filigree way of working and enormous precision. Extremely fine threads are used, and the operators wear special magnifying spectacles.

Sometimes there is this image of the surgeon who works like a butcher …

No, a butcher isn’t the right image at all – not for me, either, I hope. Cardiac surgery requires a very fine hand and a certain intuition.

Is a steady hand the most important criterion for being a good heart surgeon?

No, actually not. Without knowing what it means exactly – stress resistance and tolerance are certainly more important. On the one hand, you carry the responsibility to treat the patient as good as possible, on the other hand, you have to cope with the time pressure, as a swift operation is crucial in cardiac surgery. We also don’t joke around much during operation as is often the case in other disciplines of surgery. While setting the table, meaning preparing the operation, or when it is finished and the pressure falls off of us, we occasionally make jokes. But the act of surgery itself is usually a very concentrated one.

Are there moments when you become aware that you literally have the life of a human in your hands?

It’s not that dramatic. Of course, I am nervous before certain steps, when I know I could kill the patient in the worst case if I make a mistake. For example, air could get to the brain through the vascular system and lead to a stroke, or when vital structures in the heart or the big vessels are damaged.

How does it feel to look at the heart of person and operate on it?

In my time dealing with the heart my perspective has changed many times. It has become sharper, I can clearly see how to touch different tissues. As a comparison: For me, a Persian carpet was just a carpet until my father-in-law, who is fascinated by carpets, explained how complex the structure behind it is – the same goes for the heart.

Did you always want to become a heart surgeon?

I wanted to become a plastic surgeon for a while. But I thought being a heart surgeon would not work with my life model. Parallel to my studies I worked as a model, played in a big band at home in Upper Austria – I was worried I would have to give all of this up for the job.

As a model you walked for labels like Hermes and Armani, you even opened the Emporio Armani SS12 Fashion Show in Milan. Was there ever the thought of working full time as a model?

Back then, I had quite a naïve approach to the model job. I thought I might get booked just for one or the other job in Austria. But the agency recommended I should work internationally. Sure, there were times when I played with the thought of staying in the model business. The Emporio Armani show was one such moment. If the biggest agency in Milan had taken me at the time I would have probably stayed a year there. But this wasn’t the case, so I went to Sri Lanka for a semester as planned and returned with a tan. At the next fashion week everybody laughed at me because it was winter here. And in Sri Lanka you don’t really care so much about your figure. In the end modeling was not really an option for me, I’m actually not cut out for the job.

Social prestige comes along with being a heart surgeon. For outsiders, it seems unbelievable that someone operates on a heart, at the same time there is a lot of responsibility. How do you deal with this social pressure?

Usually you are celebrated as a hero. So you have to take care not to actually believe you are that hero or drift in the other direction and see yourself as pitiful and always under pressure. I receive a lot of respect and understanding from all sides. When I look at my family and friends, who work as translators or in economics, they master equally as extreme things. They tend to play it down and say when they make a mistake then perhaps some money is lost, but not a human life. Then I always say that ultimately I also have to see my job as a job, just like them.

“When someone dies in the ward or during surgery it is always a big tragedy.”

That sounds as if your profession was not more demanding than others …

The work is demanding as you take a big load home with you. Often the tragic fates that you observe from up close as well. The worst thing is when you overlooked something or made a mistake. That’s not on top of your mind on a daily basis, but when you don’t suppress it and hang on to the thought that perhaps someone was damaged because of you – many don’t do that – it is heavy but also important.

Has a patient ever died in one of your operations?

Yes, that’s exceptionally burdening and can haunt you for a very long time. When this happens the case undergoes extensive medical examination, it is analyzed where the problems were. Dealing with the close relatives is also tragic, especially when you got to know the person and were immersed in the situation for a while. Also when it was uncertain in advance if the operation would work out, as nowadays medicine allows heart surgery on very ill people as well, something that was unthinkable just a few years ago. Afterwards you naturally wonder if it was justified to carry out the operation or if it would have been better not to.

Do you become hardened by the topic of dying in time?

In cardiac surgery most patients are operated successfully and can go home soon. When someone dies in the ward or during surgery, which rarely happens, it is always a big tragedy. It concerns me as an assistant doctor as much as the long-serving, experienced colleagues. In our field medical or human failure is devastating, but it unfortunately can happen. Cardiac surgery is very standardized, there are many security measures.

“If the soul resides in the heart it would make my job rather spooky.”

Do we become a different person when we carry the heart of someone else?

There are reports that recipients notice completely different interests after a transplantation, which the patients have no explanation for. But every one of us can imagine that a heart transplantation is per se a life changing intervention. Here in our hospital, a specially trained transplant psychologist is responsible for this very sensitive psychological situation. She takes care of the patients from the waiting time to the phase after the operation.

In Christian European culture the heart is said to be the home of the soul. Is there also a medical explanation for this?

There are studies and tests exploring whether certain cells might also have other functions, if there are special nerve cells in the heart linked to consciousness. These speculations are not scientifically founded and thus have no influence on our profession. There is no medical evidence on the home of the soul.

Do you think the soul resides in the heart?

Phew, I can’t imagine it and don’t think the soul resides in the heart. If I had a heart disease, for example, and got a new heart, I would certainly not change in my complete personality. Just the thought alone would make my job rather spooky – when you not only transplant a heart but also a soul.

Cordial thanks for the talk!